Why That Stack of Candy is Actually Art

Meet the artists who turned ordinary items into profound art pieces

Imagine walking through a museum.

First, you see Joaquín Sorolla's serene landscape. The brushstrokes capture the light and essence of the Spanish countryside.

Next, you step into a room where Francisco Goya's "The Third of May 1808" commands your attention. The vivid colors and dramatic scene pull you into a world of intense emotion and historical significance.

Then, you turn a corner and find something unexpected—a neat stack of candy on the floor by Félix González-Torres. It's stark, simple, and completely different from the previous rooms.

What is this? Can this really be considered art? It lacks the technical skill of Sorolla and the emotional power of Goya. It doesn't take you anywhere but right here, in this quiet, almost cold gallery space.

How can this be art, and what should we make of it?

González-Torres made this work in 1991. In the years leading up, the Berlin Wall had fallen, the Soviet Union was dissolving, and the AIDS crisis was at its peak. The decade's identity as one of global change and cultural questioning was forming. And the art of the time reflected a widespread questioning of tradition.

There was pop art, minimalism, performance art, and Fluxus. Paintings, when they did happen, were coming off the wall and invading your space. And there was also this thing that González-Torres was doing, which came to be called conceptual art.

In 1969, artist Joseph Kosuth explained it like this:

"The art I call conceptual is such because it is based on an inquiry into the nature of art itself. It means that all the planning and decisions are made beforehand, and the execution is a perfunctory affair. The idea becomes the work of art."

For Kosuth, this often meant creating textual works that posed questions about art and language. Even after Kosuth's pieces are created, the focus remains on the concept rather than the physical execution. The resulting works can be thought-provoking, but it's not the individual touch of the artist that makes them so. It's the idea supported by proper execution.

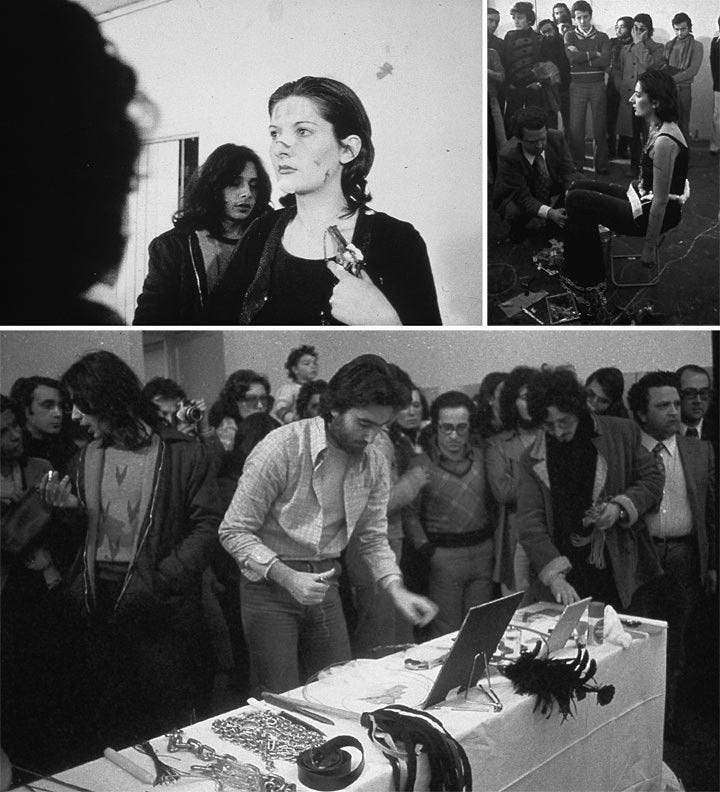

In a 1970 piece, Marina Abramović challenged herself to sit silently while the audience was invited to interact with her using various objects. She said of it, "I'm almost not an 'I' anymore; I put myself in the service of this experience."

And sometimes it was actually machines that made the art. Nam June Paik's "TV Buddha" came to be when he set up a statue of Buddha watching its own image on a closed-circuit TV, turning the TV into a dynamic, changing sculpture.

The physical presence is secondary to the idea that brought it into being. You didn't have to be there to see Portuguese artist Helena Almeida's interactive sculptures. She took photos and made films of them and shared them widely. And when you see one of those photos or hear about it in a YouTube video, your understanding isn't really distorted or diminished.

This period marked a shift towards dematerialization in art. It wasn’t often as literal as American artist Chris Burden’s 1971 performance “Shoot,” in which he had himself shot in the arm by an assistant as part of a gallery performance. Because materials were almost always involved, it’s just that they were often ephemeral—notes, performances, recordings, or at least not the primary concern.

Steel became a medium for deep exploration in the hands of Spanish artist Eduardo Chillida, who in the late ‘60s focused on the relationship between space and material. Chillida’s works, often monumental iron and steel sculptures, were designed to endure and interact with their surroundings.

Unlike the fleeting nature of some conceptual art, Chillida’s sculptures were intended to be permanent fixtures that invite ongoing engagement and contemplation.

More characteristic of conceptual art is Japanese artist On Kawara’s “Date Paintings,” for which he painted the date on canvases and documented each one. The actions were documented, and what you see here is the final piece.

Kawara said at the time:

“The world is full of objects, more or less interesting; I do not wish to add any more. I prefer simply to state the existence of things in terms of time and/or place.”

Which brings us back to those candy stacks because what González-Torres is doing is pointing out the existence of things in time and place. Taking it a few steps further than when René Magritte reminded us that this painting of a pipe is not a pipe.

When we look at this pile of sugar cubes, we know it's not a building material. But we're probably not thinking about how it's a kind of sign we recognize as indicating consumption.

Just as a written description is a verbal sign that points to something in the world and a photograph is a visual sign that points to something that is or used to be in the world.

Which of these sugar cubes do we perceive to be more real than the others, especially now that these are in a museum collection and will likely never be used again?

If this putting every day stuff in a museum sounds familiar, it's because Marcel Duchamp, who made conceptual art way before it was cool or even had a name. In 1917, Duchamp submitted a porcelain urinal signed "R. Mutt" to an art exhibition, calling it "Fountain." Although, he stole the concept from Baroness Elsa von Freytag-Loringhoven. His readymade was art because he said it was and because he put it in a gallery. González-Torres's operation here is similar. He said, "The art consists of my action of placing this activity in an art context."

But the art context didn't have to be a gallery.

Sure, there were exhibitions that chronicled this kind of art but more often the art was its own means of distribution.

American artist Seth Siegelaub thought of his "Xerox Book" as an exhibition venue in itself, giving each artist included 25 pages to make a work that responded in some way to the format.

On Kawara made art by documenting his everyday life and mailing news of it on postcards to friends, acquaintances, and art collectors.

Eleanor Antin photographed herself naked every morning to document her weight loss of 10 pounds over the course of 37 days. And Mary Kelly recorded the activity of taking care of her young son, reflected on motherhood and conversations with him, and eventually allowed him to scribble over her documentation.

Conceptual art was out in the world, often blending with activism. The Art Workers Coalition organized in 1969 to agitate for artists' rights and against Vietnam, racism, and sexism. But for the most part, conceptual art was political not in its illustration of current events but in its commitment to rethink the status quo.

There was a worker mentality and pragmatism to much first-generation conceptual art. A deadpan recording and structuring of life, almost aggressively unartful, that replaced the careful consideration of composition and form and flourish normally associated with art and artists.

American artist Edward Ruscha's book "Twentysix Gasoline Stations" recorded exactly that, 26 gasoline stations. German artists Bernd and Hilla Becher took straightforward pictures of water towers. That's what they did, across years and continents. There was no trickery at play, no need for an interpreter.

What's needed for this kind of art, more than interpretation, is a shift in perspective. An opening of a door that allows an idea by American artist Lawrence Weiner to be art. "Two Minutes Of Spray Paint Directly Upon The Floor From A Standard Aerosol Spray Can" is exactly what it sounds like. A wall that reads, "A bit of Matter and a Little bit more".

Or a sign to be art, like this one by German artist Joseph Beuys.

It's up to us.

Do we want to play a role and call this art?

We're used to art galleries being places where visual experience reigns supreme.

But conceptual art asks us to understand the gallery experience as never having been purely visual—always informed by our other senses, the art's context, and the invisible perceptual operations happening in our minds to process it.

Conceptual art has given us new words to describe what we encounter and new levels of interaction. We can still appreciate a masterful painting, but in a world after conceptual art, we do so with our blinders off.

Once conceptual art lessons have been internalized, we see that this is not a canyon. This is not what happened in a starry night. Conceptual art still lives and blends with many other ways of making. But it's a slippery art, one that avoids living in just one spot, one that resists ownership and being turned into other luxury goods.

Until next time. By any art necessary.