Unveiling the Taboo (Vol II): Ireland's Censored Artistic Heritage

Exploring the Resilient Journey of Irish Art Through Centuries of Cultural Censorship

Tracing the Shadows of Censorship and Banned Art in Ireland's History, From Past to Present

Ireland has bestowed upon me an abundance of treasures: a flourishing career, the very language with which I pen these words to you today.

Ireland has enriched my life with unparalleled friendships and placed in my journey the most extraordinary human being I have ever encountered, my wife.

This land has broadened my zeal for the arts at large, igniting a particular fervour for music and literature.

Moreover, Ireland has imparted to me a profound understanding that grasping history is the cornerstone of forging the future.

As such, this post comes directly from the left atrium of my heart.

Only a few weeks ago, I delved into the intricate narrative of art censorship in Spain, the country of my roots. Reflecting on this, I found it both fitting and imperative to explore and honour the same theme within the country I am proud to call my everlasting home. Portugal, and Denmark will follow.

In Ireland, stories are as complex and rich as its history; there exists a compelling narrative that often lies in the shadows yet is as integral to the cultural fabric as the stories of its legendary heroes.

This post tells a short version of the story of censorship and its impact on the arts in Ireland. This tale traces the contours of Ireland's journey from a past punctuated by suppression to a present that seeks to balance freedom of expression with the echoes of its historical constraints.

The history of censorship and banned art in Ireland is not merely a chronicle of prohibition; it is, more profoundly, a testament to the indomitable spirit of Irish artists and the resilience of their creative expression.

From the ancient bards, whose lyrical tales carried the essence of Irish culture, to modern writers and painters, whose works have sometimes chafed against societal norms and government edicts, Irish art has continually navigated the choppy waters of censorship.

To understand this complex relationship, we must tap into Ireland's past, where the interplay of religion, politics, and culture often set the stage for censorship. In the shadows of this history, we see the silhouette of a nation grappling with its identity, torn between the urge to preserve traditional values and the desire to foster artistic freedom.

The Catholic Church has historically wielded significant influence in Ireland, and its moral compass often guided what was permissible in artistic expression. Works that defied these moral standards, particularly those that explored themes of sexuality, religion, or politics, found themselves at the mercy of ecclesiastical censure.

However, it was not just religious institutions that sought to regulate art; the political landscape, particularly during times of colonial rule and the struggle for independence, played a crucial role in shaping the boundaries of acceptable expression.

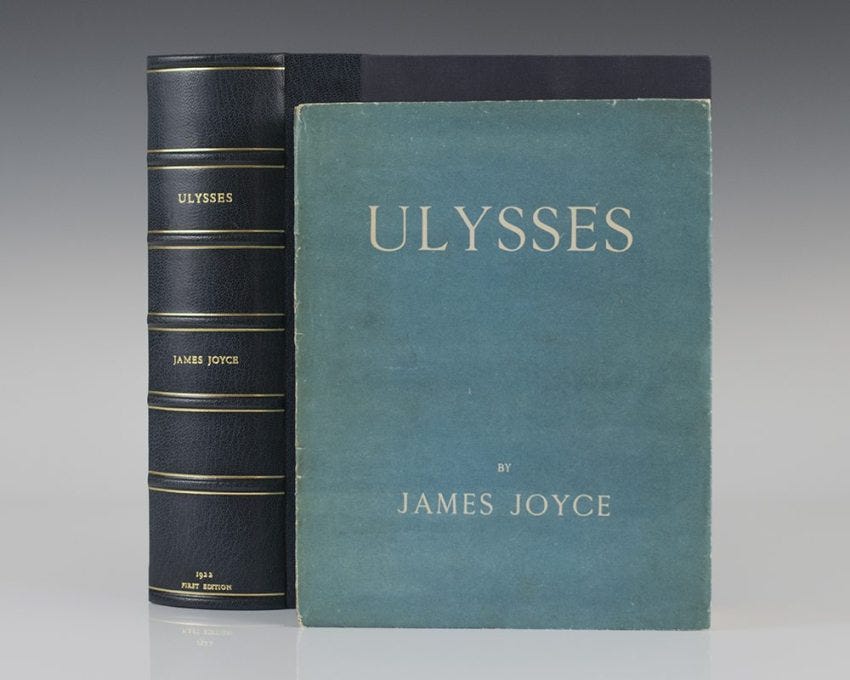

The 20th century marked a pivotal era in the saga of Irish censorship. The establishment of the Irish Free State in 1922 brought with it the Censorship of Publications Act of 1929, a legislative effort to control the influx of 'immoral' literature. I was shocked to learn that renowned works by Irish authors like James Joyce and Samuel Beckett, and international writers such as D.H. Lawrence, found themselves on the prohibited list, ostensibly to safeguard ‘public morality’ but also reflecting deeper anxieties about Ireland's cultural and national identity.

Yet, as often happens, censorship inadvertently fanned the flames of curiosity and defiance. Banned works became symbols of intellectual freedom, their allure magnified by their unavailability. Irish artists, writers, and thinkers, whether at home or in the diaspora, used their talents to challenge and critique the very systems that sought to restrain them, thus ensuring that the flame of creative freedom, though shadowed, was never extinguished.

Fast forward to contemporary Ireland, and the landscape of censorship has undeniably evolved. The relaxation of censorship laws and greater integration into the global community have opened new avenues for artistic expression, but it is still far from over.

The digital age, with its boundless reach, has further complicated the dynamics of censorship, raising new questions about the balance between freedom and social responsibility.

Literature and Censorship, a marriage of inconvenience

Continuing our exploration of censorship and banned and to add to the three literary legends already mentioned, here are some Irish writers whose works faced censorship in the 20th century.

John McGahern: John McGahern, a prominent Irish writer, faced censorship with his novel "The Dark." Published in 1965, the novel navigates themes of awakening sexuality, sexual abuse, and profanity. Its raw and honest portrayal of these subjects, especially in the context of Irish society and its conservative values, led to its banning. McGahern's work is a poignant exploration of personal and societal struggles, reflecting on the constraints imposed by the society on individual identity and expression.

Kate O’Brien: An influential figure in Irish literature, Kate O'Brien's novel "Mary Lavelle" was banned for its exploration of female sexuality and homosexuality. Published in 1936, the novel was ahead of its time, daring to address themes that were considered taboo and inappropriate by the standards of the church and Irish society. O'Brien's work is a testament to her courage in challenging the societal norms and offering a nuanced portrayal of women's experiences and identities.

Edna O’Brien: Renowned for her frank and evocative storytelling, Edna O'Brien also faced the brunt of censorship in Ireland. Her 1960 literary debut "The Country Girls," which faced a ban by the Irish censorship board and was publicly burned by a parish priest, remains controversial. Her works, which often explored themes of women's lives and sexuality, pushed the boundaries of what was deemed acceptable in Irish literature. Her narratives provided a bold and unapologetic look into the complexities of female experiences, challenging the conservative norms of Irish society. The censorship of her work highlighted the tension between traditional values and modern artistic expression.

Eric Cross: His book "The Tailor and Ansty," about the life of Irish tailor and storyteller Timothy Buckley and his wife Anastasia, was banned for its 'indecent' general tendency, presumably due to uninhibited references to animal reproduction.

Ben Kiely: Faced censorship for several of his novels, including "In a Harbour Green" and "Honey Seems Bitter," which delved into themes of sexual relationships and infidelity, challenging the prevailing moral standards of the time.

These authors, through their bold and courageous narratives, not only faced censorship but also played a crucial role in questioning and eventually reshaping the cultural and moral landscape of Ireland. Their works, once suppressed, have become significant in understanding the evolution of Irish literature and its relationship with societal norms and censorship.

However, the influence of societal norms, religious beliefs, and political conditions on art and artists in Ireland cannot be underestimated. Here are some insights into the broader context of Irish art and how it intersected with these forces:

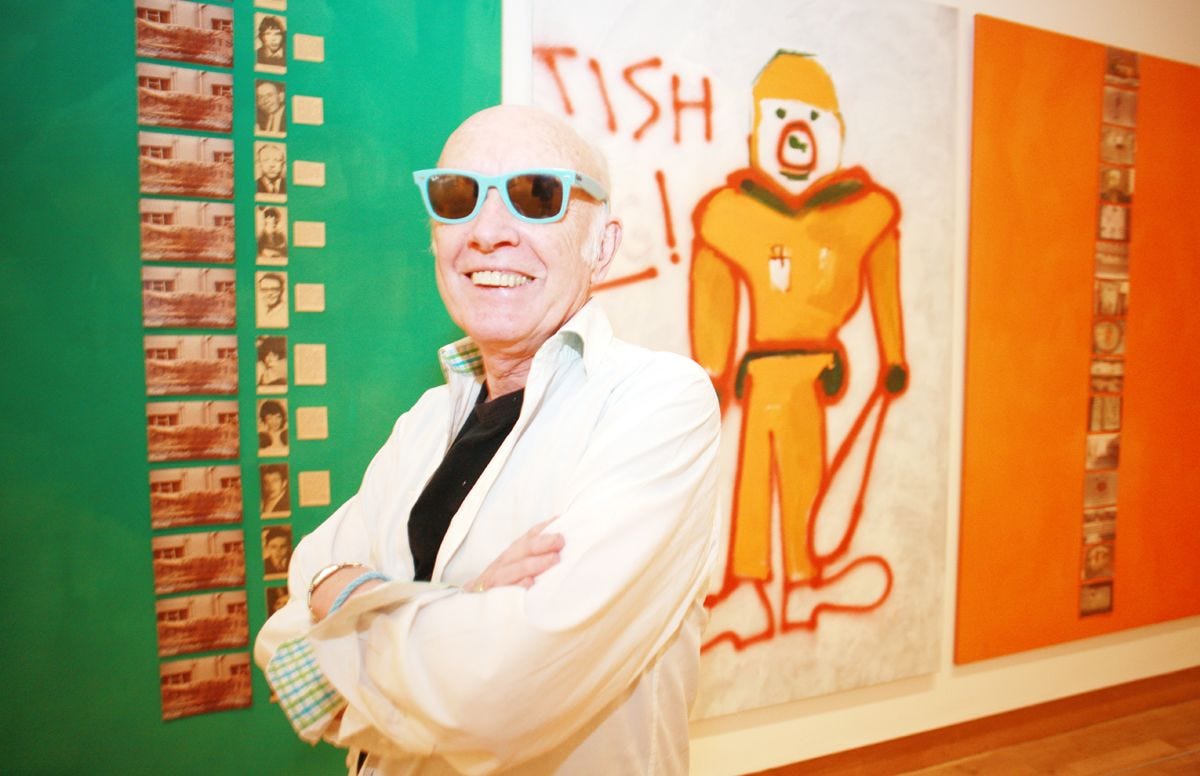

In 1978, the renowned artist Conrad Atkinson, celebrated for his fearless exploration of political and social themes, created the impactful piece "Silver Liberties" to mark Queen Elizabeth's Silver Jubilee, it then faced a ban at the Ulster Museum due to its bold representation of the Bloody Sunday massacre and police brutality in England, depicted on canvases colored in the Irish tricolour and a fourth black panel.

TAKING LIBERTIES: Conrad Atkinson in front of his once-banned but then celebrated work, \'Silver Liberties - Souvenir of a Wonderful Anniversary Year\', at the Ulster Museum in 2014. Source: Belfastmedia George Bernard Shaw and Lady Gregory's Collaboration: The staging of George Bernard Shaw's play "The Shewing Up of Blanco Posnet" in collaboration with Lady Gregory led to a significant controversy. The play, intended to antagonize the British censor, sparked a defiant campaign against censorship, which was a part of a tradition of anti-censorship activity in Ireland. This controversy is indicative of the broader challenges Irish artists faced in pushing against societal and governmental constraints.

Father Michael O’Hickey's Campaign for the Irish Language: Father Michael O’Hickey's advocacy for making the Irish language a requirement for entrance to the National University was controversial. His dismissal from the chair of Irish at St Patrick’s College, Maynooth, and the subsequent appeal to Rome, reflect the complex interplay between art, language, and national identity in Ireland.

Roger Casement's Afterlife and Controversy: Roger Casement's story, while primarily political, had significant implications for Irish art and culture. The controversy surrounding his so-called Black Diaries, which contained descriptions of homoerotic encounters, demonstrates the intersection of art, politics, and social norms in Ireland. The debates around Casement's life and diaries reflect changing attitudes toward sexuality and civil rights in Ireland, which undoubtedly influenced Irish artists and their work.

The Evolution of Censorship Laws in Ireland

The 20th century in Ireland was a period of immense social and political transformation, which profoundly impacted the landscape of Irish art. Artists found themselves navigating a complex terrain, heavily influenced by Ireland's post-colonial history, ongoing political upheaval, and a deeply entrenched religious environment. This unique backdrop played a significant role in shaping both the thematic focus and the methodologies adopted by Irish artists, making their work a reflection of the broader societal changes.

One of the most significant legal constraints on artistic expression was the criminalization of publishing or speaking blasphemous material, a mandate from the 1937 Constitution. This law, which remained in effect until January 17, 2020, was seen as a reflection of the intertwining of state and religious doctrine in Ireland. The law's elimination followed a 2018 referendum, marking a pivotal shift in the relationship between the state, religion, and freedom of expression.

A defining moment in the evolution of Irish society and art was the "Repeal the 8th" campaign. This significant movement, aimed at removing the Eighth Amendment from the Irish Constitution, brought to the fore the issues of women's rights, health, and bodily autonomy. Introduced in 1983, the amendment equated the right to life of the unborn with that of the mother, effectively imposing a near-total ban on abortion. The campaign, culminating in a successful referendum on May 25, 2018, saw widespread participation from artists and activists, some of whom faced censorship for their support of the repeal.

This movement not only changed legislation but also ignited a dialogue in the arts about women's autonomy and rights.

Fast forward to January 2024, and we see further progression in the liberalization of artistic expression with Irish Minister for Justice Helen McEntee's proposal to repeal the Censorship of Publications Acts.

These nearly century-old acts, which had once given the state broad powers to censor materials deemed indecent, obscene, or overly focused on crime, were reviewed and found to be obsolete in the context of contemporary societal values and policies.

This repeal, while moving away from the outdated aspects of Ireland's past, importantly does not impact the prosecution of offences related to child abuse or abusive material. The process will include the archiving of records, ensuring that the historical and cultural significance of this period in Irish art and censorship is preserved and understood.

These developments, from the abolition of blasphemy laws to the repeal of censorship acts, reflect a broader shift in Ireland. They signal an ongoing journey towards greater artistic freedom, reflecting a society that continually reevaluates and redefines its values, policies, and the role of art in voicing and shaping public discourse.

But let's not view the history of banned and censored artworks in Ireland solely as a narrative of restrictions and prohibitions. It's also a story of resilience and adaptability in artistic expression. It illustrates how art has continually influenced and been influenced by Ireland's historical and contemporary societal shifts.

Thank you for making it this far! If you enjoyed the content, please share the newsletter or the link with your dear ones.

Bonus: as you have reached the very bottom of this digression, I wanted to reward you with an incredible poem written by Alan Dugan, an Irish poet.

Ireland was better in its dream, with the oppressor foreign. Now its art leaves home to keen and its voice is orange. It is a sad revolt, for loving's health, that beats its enemy and then itself Now that Irishmen are free to enslave themselves together they say that it is better they do worst to one another than have the english do them good in an exchange of joy for blood. A just as alien pius blacks their greens of lovers' commerce; rehearsing victory, they lack a government to fill its promise. Worse, law has slacked the silly harp that was their once and only Ark out, and I am sorry to be flip and narrowly disrespectful, but since I wade at home in it I stoop and take a mouthful to splatter the thick walls of their heads with American insult! Irish sense is dead

You can immerse yourself in the experience of hearing him recite this poem—a treasure I unearthed within the archives of the University of Arizona.