Empathy Through Art: Bridging Human Connections

Explore how art evokes empathy through powerful examples like Michelangelo's Pietà and contemporary photography, feel the emotional impact of art across cultures and eras.

Empathy is the ability to understand and share the feelings of another person. It involves taking on another's perspective, sensing their emotions, and responding with compassion. This fundamental human capacity enables us to connect with others, build relationships, and foster social harmony.

"Empathy is not just listening, it's asking the questions whose answers need to be listened to. Empathy requires inquiry as much as imagination." - Celeste Headlee, journalist

Empathy allows us to engage deeply with the human world and psyche, and art, in all its forms, can significantly stimulate this engagement. Here are a few examples:

Empathy Boxes by Philip K. Dick: In the novel "Do Androids Dream of Electric Sheep?", fictional devices called Empathy Boxes allow users to share and experience each other's emotions.

Human Flow by Ai Weiwei: This powerful documentary captures the scale and personal impact of the global refugee crisis, taking viewers on a journey to 23 countries and showcasing the desperate search for safety, shelter, and justice faced by millions of people forced from their homes due to war, famine, and climate change.

Fons Americanus by Karen Walker: A powerful centerpiece at Tate Britain, London. Inspired by the Victoria Memorial fountain, Walker reimagines this iconic monument to critique colonialism's violence and exploitation. The towering fountain features allegorical figures referencing the transatlantic slave trade, imperialism, and racial oppression, blending mermaids and Poseidon-like figures with colonial symbols like ships and weapons.

When you experience these artworks, it’s nearly impossible not to feel for their subjects. We empathize with them, sharing their pain. Our pulse may quicken, and we might even mirror their behaviors, bracing ourselves for the inevitable impact.

Art's power to connect us with others and evoke emotions is a major reason people are drawn to it. If we allow it, art can break through the jaded armor of our modern existence, inviting us to experience the emotions of someone who might live far away or in a different era.

The Beginning of Empathy

The concept of empathy has a long history that spans multiple disciplines, including aesthetics, psychology, and philosophy. The term "empathy" was coined by Robert Vischer in 1873, originally referring to the projection of human feeling onto the natural world.

The concept gained prominence in the late 19th and early 20th centuries through the work of philosophers such as Theodor Lipps and psychologists like Edward Titchener, who translated Lipps' term "Einfühlung" (feeling into) as "empathy" into English in 1909.

Empathy was heavily influenced by the writings of David Hume and Adam Smith, particularly their ideas on moral philosophy and the nature of human sociality. Hume's notion that "the minds of men are mirrors to one another" highlights the idea that humans can resonate with and recreate the thoughts and emotions of others.

Empathy as an Art Catalyzer

Religious Art

Religious art has long stirred emotions and empathy in viewers. One remarkable example is Michelangelo's Pietà, a marble sculpture from the late 15th century housed in St. Peter's Basilica in Vatican City.

Michelangelo's Pietà emphasizes the serene and tender sorrow of Mary, rather than a dramatic display of grief. Her youthful, peaceful expression invites viewers to contemplate her suffering in a profound and personal way. Jesus, depicted with meticulous anatomical precision, appears lifeless and delicate in his mother's arms, with subtle wounds focusing on the tragic beauty of his sacrifice. The smooth, polished marble enhances the realism and emotional impact, allowing viewers to feel the sacredness and gravity of the moment.

During the Renaissance, artists like Michelangelo sought to humanize religious figures, making them more relatable to the faithful. This shift reflected a broader spiritual movement towards personal devotion and empathy for the human aspects of divine figures.

Islamic Art

Emerging from the Islamic tradition is the portrayal of the Prophet Muhammad's Miraj (Night Journey), an event deeply rooted in empathy and spiritual significance. One renowned depiction can be found in the 16th-century Persian manuscript of the Khamsa by Nezami, illustrated by Sultan Muhammad.

This illuminated manuscript vividly portrays the Prophet Muhammad's ascension to the heavens, guided by the angel Jibril (Gabriel). In this journey, the Prophet meets various prophets and angels, gaining profound spiritual insights and witnessing the plight of souls. The Miraj is often depicted with great sensitivity, emphasizing the Prophet's role as an intercessor and compassionate leader deeply concerned with the welfare of his followers.

The Miraj is not just a personal spiritual journey but a metaphor for the Prophet's deep empathy for humanity. By undertaking this journey, Muhammad is shown experiencing and understanding the struggles and suffering of people, reinforcing his role as a merciful and empathetic guide for the Islamic community.

Indigenous Perspectives

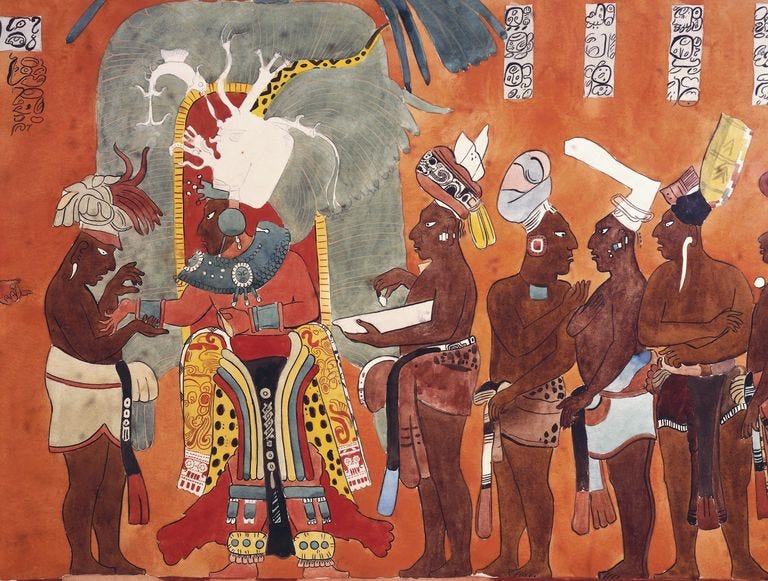

In the Classic period of Mayan civilization, many artistic works conveyed the deep spiritual and social values of the Mayan people, often highlighting themes of suffering and resilience. One compelling example is the murals of Bonampak, discovered in a temple in Chiapas, Mexico, dating to the late 8th century.

The Bonampak murals are renowned for their vivid depiction of Mayan life, including scenes of battle, ceremony, and ritual.

One particularly moving segment of these murals shows the aftermath of a battle, portraying not only the victorious warriors but also the captured and suffering prisoners. The expressions and postures of the captives—bound, wounded, and awaiting their fate—evoke a profound sense of empathy for their plight.

These murals stand out for their realistic and humanizing portrayal of the prisoners. The artists conveyed a wide range of emotions, from fear and despair to resignation and courage, inviting viewers to connect with the captives on a personal level and reflect on the human cost of conflict and the shared vulnerability of all people.

Photography and Empathy

Photography can be an extremely powerful tool for stimulating empathy. In post-war Europe, several photographers captured the continent's recovery and the human condition.

In April 1945, Henri Cartier-Bresson captured a poignant moment in Dessau, Germany. His photograph, "The Interrogation," depicts a woman being publicly exposed as a Nazi collaborator.

The scene unfolds with the woman accusing her accuser, seated at a desk, while a crowd gathers to witness the ordeal. This powerful image not only documents the immediate aftermath of World War II but also highlights the complexities of guilt, shame, and accountability. Cartier-Bresson's lens captures the emotional intensity of the moment, inviting viewers to reflect on the human cost of war and the consequences of collaboration.

In the 1950s, Robert Doisneau's photographs of Parisian life brought attention to the everyday struggles and joys of the city's inhabitants. "Accordion Girl" is a photograph by Robert Doisneau, taken in the early 1950s. The image features a woman, Pierrette d'Orient, playing the accordion on the streets of Paris. Doisneau worked with Pierrette for a day, capturing several photographs of her playing the accordion in different settings. This particular image is notable for its composition, with Pierrette out of focus in the distance and the accordionist in the foreground. The photograph showcases Doisneau's ability to capture the essence of everyday life in Paris, highlighting the beauty and humor in the mundane but also the hardship of post-war France.

In the 1980s, Sebastião Salgado addressed the question of how to document the hardship of others and inspire empathetic responses through his work Workers, which captures the dignity and hardships of laborers across the globe, including Europe. Salgado's black-and-white images emphasize the resilience and strength of his subjects, encouraging viewers to see beyond their struggles to their inherent dignity.

More recently, Dutch photographer Rineke Dijkstra has explored the limits of portraiture and its capacity to inspire empathy with works such as her series Beach Portraits. Taken between 1992 and 2002, these portraits of adolescents on beaches in Europe capture the vulnerability and strength of her young subjects. Dijkstra’s empathetic lens invites viewers to connect deeply with the individuals, contemplating their inner lives and the universal experience of growing up.

These photographers have used their craft to create compelling narratives that move beyond mere documentation, encouraging viewers to engage empathetically with their subjects and to reflect on broader social and historical contexts.

Empathy Initiatives

Empathy isn't limited to feeling the pain or loss of others. We can also connect with emotions like passion, joy, or contentment. Moreover, we can empathize with people worldwide facing non-life-threatening but significant issues similar to our own.

An inspiring example is the artist collective Inside Out Project, founded by French street artist JR. This global initiative invites people to share their portraits and stories, turning them into large-scale public art installations. In various cities, these portraits showcase diverse emotions and experiences, fostering empathy by highlighting our shared humanity.

In Brazil, the group painted vibrant murals of local residents' faces and stories, transforming urban spaces and encouraging empathy between different community members. These murals capture joy, resilience, and pride, prompting viewers to reflect on their own lives and connections with others.

Similarly, the Australian collective Big hART uses art to build empathy across cultural and social divides. Their project, "Namatjira," celebrates the legacy of Aboriginal artist Albert Namatjira while addressing contemporary issues faced by Indigenous communities. By sharing Namatjira's story and the vibrant art of his descendants, Big hART fosters understanding and appreciation between Indigenous and non-Indigenous Australians.

These initiatives reveal art's true power: bridging divides, sparking empathy for a spectrum of emotions, and building deeper connections among diverse people.

Final thoughts

Our grasp of empathy is still a work in progress, without a single, clear definition. But the art we've looked at today shows its many faces.

Empathy thrives in the artist's mindset as they ponder their subject and audience. It also lives in their intent, striving to ignite empathetic responses in those who experience their work.

Art, at its best, doesn't just tell a story; it invites us to feel and connect on a profound level.

Every piece of art has the potential to ignite empathy.

It offers a glimpse into another person's world, whether they're a contemporary or from another era.

When we truly engage with art, empathy becomes essential.

We ask who created it, where, and why. What drove them to express these ideas?

This curiosity deepens our understanding of others, urging us to see their lives as rich and significant. Art compels us to recognize the complexity and reality of others' experiences.

If that’s not a powerful reason to explore art, what is?

Until next time, by any art necessary.